Magnification of grains of refined sucrose, via Wikipedia

In learning programming languages, specifically Ruby, I was introduced to the applied concept of “syntactic sugar”. Prior to Ruby, my limited exposure to server-side development was some PHP and a little bit of Java a few years back, and let’s just say the pot of java tasted close to black as a programmer writing code. In computer science classes in highschool, we were taught that expressions were to be written a certain way all the time. The syntax was rigid and verbose, and we were taught that’s just the way it was. Although I liked programming back then, it felt tedious and cumbersome. I simply thought this was a programmer’s lot: to parlay with the computer like a foreign delegate from the United Nations, where nothing goes wrong if you rehearse the language correctly, but the predictably formal exchange was always cordial and stuffy. Black coffee.

Truth be told, there’s something to be said for the predictability of statically typed, strict languages. There’s a comfort in knowing that a particular way of doing things is how things are to be done all the time, and there’s bound to be less errors. However, that made translating statements from my brain to the keyboard slow, with a lot of repetitious, humanely-unnecessary typing. That is, the language needed things typed out certain ways for the computer to understand what I was saying, while I, the human, not needing that degree of repetitive verbosity for my understanding, was always left with no choice but to appease the computer.

Enter Ruby, which changes a lot of this for me. This is, in a very large part, due to this concept of “Syntactic Sugar” (aptly named for how sweet it is).

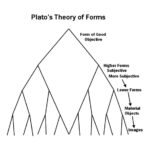

Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto, in creating Ruby, built the language with the programmer’s enjoyment in mind. The flexibility of its syntax therefore makes it incredibly fun to write in (it’s delicious if you will) without compromising the specificity of how the interpreter reads your code. Ruby abstracts away often occurring verbose expressions to simpler commands, with built-in human-readable shortcuts. At first, I didn’t understand the concept, because I thought the lessened lawfulness of the language would make using it more errorprone and ambiguous. However, I was quick to learn that there is a difference between abstraction and ambiguity.

As Edsger Dijkstra said, “Being abstract is something profoundly different from being vague… The purpose of abstraction is not to be vague, but to create a new semantic level in which one can be absolutely precise.”

Edsger Dijkstra, 1963

Take a look at this code in JavaScript for performing an action 3 times:

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

console.log("One cup of JavaScript please, black.");

}It’s fairly readable, but it isn’t so abstracted. We’re explicitly stating what we’re doing, declaring a variable (i) to keep track of an incrementing state, until it reaches “3,” in order to carry out our task that amount of times. There’s no other way to express this, and the programmer is left needing to type out a similar block each time they want the same behaviour (unless they use a precompiled library).

Here’s the same task in Ruby:

3.times do

puts "Ruby is aspertame-free!"

endAll of the explicit logic is abstracted away to instead make it perfectly clear what we want our program to do: put out the desired phrase 3 times. Of course, ‘times’ is really a method which is being called on the object of the integer ‘3’ using dot notation, but Ruby can be written in such a way so that users not yet knowing its internal mechanisms can make sense of the program flow more easily, and thus, code faster, lighter, and more naturally.

As an aside for the next example, recall that Ruby is an Object Oriented language, and as an extension of this, everything in Ruby is an object. So called ‘classes’ are objects that are both blueprints and factories that create more objects (called ‘instances’) of that class’s kind (each instance of the class contains information (data attributes) and behaviour (methods) as described by the class blueprint). Let’s say we’re creating a User class to represent users in our app, and each instance of a user has to have a screen name, which we’ll place in a variable called @screen_name.

In the body of the User class, we’d create a so-called ‘setter’ method so instances can call upon this method to ‘set’ the value of their screen names. The method could be called anything, like set_name, as seen below:

def set_name(name)

@screen_name = name

endRuby however allows us to define methods ending with an equal sign(=). We can replace set_name with a method called name= like so:

def name=(name)

@screen_name = name

endname= does exactly what set_name did, and despite the, at first, odd naming convention, you can call it just like any other method using dot notation, as below:

new_user.name=('Wintermute')In this case, the string ‘Wintermute’ is the argument passed into the name= method, which sets the @screen_name variable equal to that value. However, there’s a reason for the equal sign naming convention. Ruby allows us to forgo the parentheses for methods which accept only one argument. So you can instead do this:

new_user.name = 'Wintermute'The interpreter knows what you’re doing when it sees the spaces between “name” and “=”, reading the method as we’ve defined it: ‘name=’. The string ‘Wintermute’ is being passed into the method as an argument, but with the parentheses abstracted away, once again, the programmer more easily understands what they’re doing because the code is written more linguistically similar to how humans speak: ‘name equals Wintermute.’ The syntax is cleaner, and its meaning more clear, when unnecessary operators can be excluded.

A last quick example of the concept is the use of conditionals in Ruby. While the structure of conditionals (like ‘if’ statements) are pretty well known and similar in many languages,

if foo

puts "bar"

endRuby allows you to make a simple placement change that makes blocks of code shorter, more readable, more elegant and laconic.

In fact, you can type out the same thing above, like so:

puts "bar" if fooSweet.

I strive to write my code and interfaces just as intuitively as Matz has for Ruby.

You made some good points there. I looked on the web for additional information about the issue and found most individuals will go along with your views on this website. Kacey Trev Abbye