“It’s functions all the way down.” – Ancient Internet Proverb

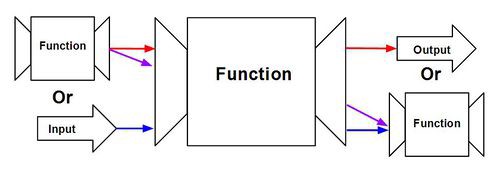

One of the most powerful things about JavaScript is that it treats functions as first-class citizens. That means, unlike other programming languages, functions in JS are entities which support mostly all of the operations available to other entities. Functions can therefore be assigned to variables, stored in other data structures (e.g. arrays or objects), and most excitingly, they can be passed into other functions as arguments, and they can be returned from within the execution of other functions too.

These are the so-called Higher-Order Functions, and this pattern would be really weird in a language like Ruby that’s purely object oriented. JavaScript however plays fast and loose with which programming paradigm you pick to build software. Depending on your needs at the time, you can program procedurally or in an object-oriented (or more specifically, prototypal) manner, or even a mix of both. If used smartly, this can be really freeing and useful.

Procedurally, you can get crazy with your functions in JS, creating modular super functions and function factories by utilizing things like closures. In this way, as opposed to Object Orientation where methods feel like discrete behaviours of particular objects, functions in JavaScript can feel more like independent lego blocks that you can mix, match, modify and apply creatively to solve many problems. One very powerful pattern uses this characteristic of JavaScript to save a lot of time and keystrokes.

How To Return Functions On Declaration

A function declaration is a statement that does not return anything (undefined). All it does is store that function in memory.

function myFunc() {}

// => undefinedHowever, when the function keyword is not the first thing in a line of code, it suddenly becomes a function expression, forming the new function and immediately returning itself.

(function myFunc() {})

//=> f myFunc() {}

// or put an anonymous function expression into a variable so we can refer to it later

const myFunc = (function () {})

//=> undefined

myFunct

// => f () {} Now we have a way to return functions from variables (Side-note: Function expressions don’t get hoisted like function declarations do. Because functions don’t typically change within programs anyway, it’s a good idea to declare new functions within variables using the ‘const’ keyword (which also keeps block-scope) instead of just declaring them as statements. That way, you get the intuitive scoping that ‘const’ gives you, as well as the instant function return).

Procedural JavaScript With Closures & Encapsulation

We now know that we can return functions upon declaration. We can also put functions in other functions, so, we can also return functions from other functions. Therefore, we can create a function who’s job is to assemble other functions.

const createDivisibleFunction = function (divisor) {

return function (num) {

return num % divisor === 0;

};

};The function createDivisibleFunction() takes an argument, divisor, and has another function within it, which also takes an argument. We can invoke this function with the divisor argument, and the function within it is returned. Not invoked just yet, but simply returned. Because we passed in an argument (divisor) to its parent function at the time of the inner function’s declaration/returning, the inner function that is returned retains access to that outer argument via what is called a closure. It has ‘closed in’ on the variables present in the scope of its declaration.

// Is 6 divisible by 3?

createDivisibleFunction(3)(6)

//=> true

// Is 5 divisible by 3?

createDivisibleFunction(3)(5)

// => falseRemember, we can put a function in a variable. If we invoke this particular function with a divisor argument within a variable, that will forever tie that particular function invocation to a particular divisor argument. Logically, we can also create multiple variables with multiple versions of this function, each one individually tied to a different divisor. In this way, we can invoke each permutation of the function with different inner arguments depending on our needs.

const divisibleBy3 = createDivisibleFunction(3);

const divisibleBy5 = createDivisibleFunction(5);

divisibleBy3;

// => f (num) { return num % divisor === 0; }

divisibleBy5;

// => f (num) { return num % divisor === 0; }

divisibleBy3(9);

// => true

divisibleBy3(10);

// => falseThe divisor argument is now encapsulated, abstracted away from the outer world so we no longer have to worry about it. In fact, we can’t even change that variable anymore in any of the different permutations of the original function – it has become an encapsulated inner feature of that mini machine, safe from prying hands.

Closures and encapsulation enable function factories. We can create different sub-functions out of a singular master function factory, which is a very useful pattern to avoid code bloat and repetition when we need many similar but slightly different functions.