Gamification is defined by UX designer and researcher Sebastian Deterding (2011) as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts.”

When you’re playing a game, you’re engrossed as that character. You’re not reading about it, or witnessing it, you are the hero. That may be the imperative missing from the unexamined life. We’re already seeing it happen with smartphone apps that reward you for certain behaviours (like exercising), and even gamified realities such as escape games. In these situations, people behave differently, as if they’re more than themselves, because they’re directed by a set of rules to a defined goal that benefits a common good.

What could gamification do to augment civic actions? As Sebastian Deterding states, “Gamification may possibly provide a sustainable tool through which society is motivated to do social good,” and improve political participation. He goes on to state that “Gamification can be used to motivate users, increase their activity and prolong retention.”

Games already exist all around us, whether or not we define them as such. Meeting deadlines, making that morning meeting, keeping a budget, these are all things that are already somewhat gamified intrinsically. But what of things like voting and civic participation?

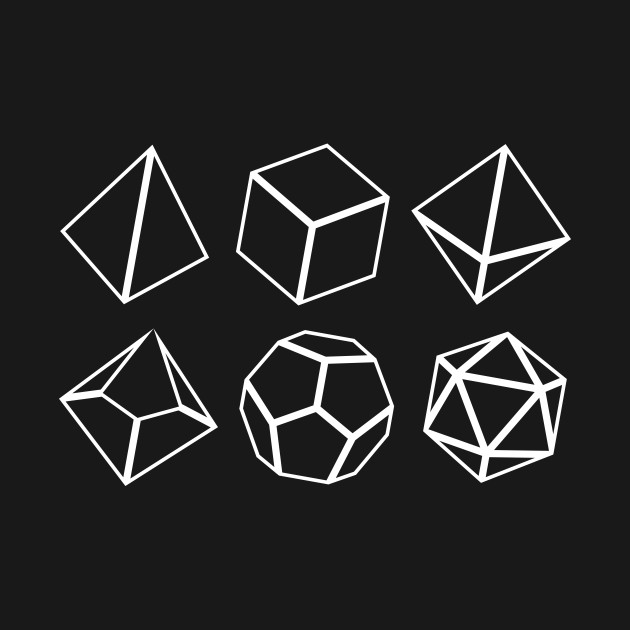

The definition of game mechanic are tools which add a structure that complements and enhances the content of a game. For instance, Points/Badges/Virtual currencies/Levels can act as motivation. The true goal of gamification is to make a certain product, application, operation, or a cause more appealing, in order to motivate the user and inspire them to return. Jane McGonigal’s book ‘Reality is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World’ says that games create alternate realities to broaden our horizons using ‘gameful’ (McGonigal’s own term for ‘playful’) ways of interacting with the real world.

Games are usually seen as escapist: on the contrary, what about ‘anti-escapist games’ that stimulate users to juxtapose their ‘real life’ with an alternate (played) one, which they also help create? Games like Sim City or Persona which create an alternate real-life filled with repeating obligations and responsibilities, but with the mundane contextualized within a bigger goal or purpose.

As a gamer, I often think that that’s the key missing ingredient in galvanizing social action: where, in the real world, is that gamer sense of being fully alive, focused, and engaged in every moment? Where is the gamer feeling of power, heroic purpose, and community? We shouldn’t use games to rebuild traditional ways of connecting, but rather, to reinvent them. A strong societal focus should be on playfulness, exploratory behavior and positive affects. A light on the importance of one’s agency and feeling that the individual makes a difference (like in an adventure game; you’re the hero, among many others, but it’s your story) – this is missing in the political and social sphere at large.

Success or failure of gamification is strongly connected with a branch of psychology called motivation theory, which heavily deals with the question of extrinsic vs. intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic Motivation is motivation from outside validators that keep you chasing that stick. Intrinsic Motivation is an internalized drive to move forward, reinforced by, among other things, a sense of self satisfaction. Traditionally, gamification has relied on extrinsic motivation (points, XP, badges) – but to see the two as necessarily binary may be myopic. The key is to see them on a continuum, and to transform extrinsic motivation into intrinsic motivation, so that people are involved not for utilitarian responses, but for emotional responses.

There is some value of extrinsic motivation: that users can enjoy the thought of immediately seeing an improvement of their ‘perceived’ situations: points can go up in value right away, as opposed to your skill level silently going up over time. McGonigal talks of something like a “sustainable engagement economy” – to motivate and reward users with intrinsic rewards. But before the action can be internalized, for users to be first motivated towards a cause, there has to be something in the gamified system, designed for users to do or solve. It shouldn’t be too difficult (to give them a sense of progress) or too easy (to give them a sense of challenge).

Gamifying Politics: Crowdsourcing Political Issues

There have been examples of gamifying civic participation. The first Massively Multiplayer Investigative Journalism Project – Investigate Your MPs Expenses – by the Guardian, used crowds to review 458,832 documents. The ‘players’ scanned forms and expenses to examine incriminating details about British MPs. It retained users because of the emotional rewards it featured, which consequently provided effective involvement. It had a “clear sense of purpose to make an obvious impact, was not too difficult, and the participants experiencing plenty of ‘Level Up’ (the feeling of having achieved a bite sized chunk of the greater goal) moments. It ended with a handful of MPs, having been proven to be corrupt not by an independent body but by the people themselves, resigning.

In this way, users don’t just clamor for change, they directly participate in political reforms. In crowd sourced political projects, civil society and the private sector can both propose solutions to their own problems. Imagine having a bunch of these projects, like Kickstarters, that people can voluntarily choose which to participate in; ones that they feel they’re uniquely qualified for – this is what makes “collaborative democracy egalitarian” – and what successful crowd projects tend to have in common (note: most of them fail) is that they are structured like multiplayer games with tiers of rewards.

It’s been observed that younger people traditionally disapprove of party structures, formality of communication, and style of debate: they’re more comfortable on a keyboard than a podium. In this sense, we may need to digitize democratic processes. McGonigal states, “The more we learn to enjoy serving epic causes in game worlds, the more we may find ourselves contributing to epic efforts in the real world.”

Another potential benefit to gamification is that since they have strict rules and conventions, they can keep track of violations of rights and (un)achievements of actors, citizens or representatives. Imagine a hypothetical Representative/Council ‘Leaderboard,’ where each action gains them points. The most popular council members are on the leaderboards – it could show real effects of political actors by showing points gained for a successful action (Note: A possible danger to gamification is that, in this same way, it can also be used to maintain the status quo, by creating worlds that aim to convince players of certain ideas and penalize them for diverging).

Briefly: Gamifying Work

Christopher Lasch’s (1979) seminal work ‘The Culture of Narcisissm’ argues that jobs are reduced to routine and that rationalized activities, and industry, aim towards ‘control and elimination of risks.’ It appears that the current working conditions and demands leave people passivized. People therefore seek ‘diversion and sensation’ in playing games – gamified real-life environments can blend working life and this ‘seeking to play.’

McGonigal states, “People require more satisfying work, a stronger sense of community, and for a more engaging and meaningful life; games can be a thoughtful escape and a distraction that can actually help us reinvent reality.”

Thank you for the sensible critique. Me and my friend were just preparing to do some research about this. We got a book from our local library but I think I learned better from this post. I am very glad to see such fantastic information being shared freely out there.. Emeline Shannan Alyose

Amazing! Its really remarkable post, I have got much clear idea concerning from this paragraph. Cariotta Mandel Christalle