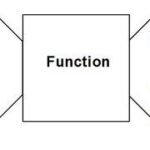

Plato’s Theory of Forms

When I started coding as a student hobbyist a few years ago, I began by seeing a computer program as a simple list of tasks for the computer to follow. I would write the logic of my first simple programs as a series of statements to be carried out in succession, like a check-list. Information, or so-called data, was passed around the program ecosystem, and procedures, or so-called functions, were things that manipulated the data. As a paradigm, this is called Procedural Programming.

Awhile later, I heard of a different paradigm called Object Oriented Programming (OOP), which I began incorporating, though what it really meant eluded me until I began learning Ruby, a purely Object Oriented language. The implementation of Object Orientation is actually fairly simple. Conceptually, understanding the why of its significance, and using it effectively, is much more difficult, but when understood, is very powerful.

The ancient Greek philosopher Plato would speak of the ‘ideal’ form. There were material forms, but there were also, according to him, higher forms. Material forms exist in the physical: like various trees scattered in a park. But in the mind, there is also a so-called ‘Platonic Tree’ – a higher, ethereal idealization of what all trees, in general, were: in essence, the ‘idea’ of a tree. This metaphysical Platonic Form of a tree, according to Plato, is what allows humans to ponder the earthly material trees, and to register and categorize them as trees. We can conceive of objects in our mind without having the object ever be in the room. In this way, we are really talking about the ‘idea’ of the object: a mental representation or model. When we speak the name of something aloud, that ‘something’ need not be physically present, but the sound waves reverberating through air create the ‘idea’ of it in the mind of the listener. Likewise, when we write down the word tree, the lines on paper are merely representative of an actual tree, and not the tree itself.

“The greatest thing by far is to be a master of metaphor.” – Aristotle

This meta-thinking is powerful, and is what has allowed us as humans to make sense of our world. It allowed Plato to extend his reach beyond the here and now, and to even conceive of the idea of the atom (from the Greek word for ‘apple’), his theorized indivisible building blocks of the universe, centuries before they could be mechanically proven as physically real. The ideas of a tree or an atom are metaphorical representations of physical things, a way to mentally model the world around us. Object Oriented Programming is just that: your code as metaphor.

“I thought of objects being like biological cells, only able to communicate with messages.” – Alan Kay at XPARC, on inventing Object Oriented Programming

Switching programming styles to Object Orientation is a powerful thing. Instead of seeing your program as merely a check-list of ordered statements with methods separate from data, you begin viewing your program as a mini universe with things that populate it. Like our universe, your program’s universe is filled with ‘objects.’ However, they aren’t physical, they’re metaphors – and unlike the physical world, in this programmatic universe, if you can conceive it, you can will objects into existence. These programmatic objects, like Plato’s idealized forms, are metaphors that model the world that you’re building. Your code suddenly goes from foreign to familiar, and this is a great conceptual leap in programming, because it helps the programmer make sense of the abstract complexity they are creating. Instead of a mesh of separate instructions, the code begins to take shape as a lawful model.

Just as in the physical world, where discrete objects are comprised of both information about itself (for example, a tree is of a certain type, with specific-looking leaves) and actionable behaviour that it can perform (trees can turn sunlight into energy via photosynthesis, and they can grow in size), objects in code have data attributes comprised of the information about them, as well as functions, called methods, which enable their behaviour. Thus, data and methods, instead of being a mesh of discrete entities in Procedural Programming, exist simultaneously inside of objects in Object Oriented Programming. Methods, as messages, can then be sent from object to object, enabling their behaviour.

In Ruby, the blueprint for a type of object is called a Class. This is like the ‘Platonic Ideal’ of trees in general, which encompass a tree’s tree-ness: the overall idea of what a tree is. Each individual tree, like a Birch Tree, or a Maple Tree, or a Palm Tree, are Instances derived from the Tree class.

The following is a rather crude, but hopefully illustrative example of the concept:

class Tree

attr_accessor :type, :leaves

def initialize(type, leaves)

@type = type

@leaves = leaves

end

def photosynthesize

puts "I'm makin' food!"

end

def grow

puts "My leaves are growing!"

end

endWith the Tree class defined, we can now instantiate different instances of tree objects in our program, as follows:

maple_tree = Tree.new('Maple Tree', 'Maple')We now have an instance of a tree that is of type ‘Maple Tree’ and has ‘Maple’ leaves, that can grow and photosynthesize through its methods.

Separate objects can also collaborate or interact with one another, creating more complex relationships and functionality within our programs. As mentioned, in Ancient Greece, Plato conceived of the idea of an atom, the building block of the physical universe. Avi Flombaum, dean and co-founder of NYC’s Flatiron School, often uses this as a basic but powerful example to illustrate OOP.

An atom modelled in Ruby:

class Atom

attr_accessor :protons

TABLE = {

1 => "Hydrogen",

2 => "Helium",

3 => "Lithium",

8 => "Oxygen"

}

def initialize (protons)

@protons = protons

end

def name

TABLE[protons]

end

endTwo instances of atoms:

hydrogen = Atom.new(1)

oxygen = Atom.new(8)Multiple atoms can create compound elements:

class Compound

attr_accessor :atoms

def initialize(*atoms)

@atoms = [ ]

atoms.map{|atom| @atoms << atom}

end

endLet’s make a common one:

water = Compound.new(hydrogen, hydrogen, oxygen)We can now water our trees.

OOP lets us make sense of our code, and create patterns and lawfulness from complexity.