As the internet becomes increasingly integrated with the world outside of just the desktop, the “language of the web” becomes even more relevant. Though when I first started learning JS, I had a tough time understanding why the language had become so widely adapted. It had a bunch of weird quirks that would continuously plague the codebases that I worked with, such as conditionals returning ‘true’ for things that I knew should’ve been ‘false,’ and variables strangely not being defined or defined as something unexpected in my function calls (not to mention it was, allegedly developed in just one week by Brendan Eich). After some reading and a lot of coding, I started understanding why these things occurred, and that understanding gave way to good coding patterns, and exposed how fun/powerful JS can be.

To solidify what I’ve learned, here are some of the oddities that repeatedly threw me for a loop (heh) when I first started learning, why they occur, and how to avoid them:

Weird Thing 1: Comparison Operators

null > 0

//=> false

null >= 0

//=> true

null == 0

//=> false

null <= 10

//=> true

null < 0

//=> false

// Don't you dare question JS's logic!The example above seems odd and nonsensical, but it’s really the result of JS’s engine being too nice and refusing to throw errors when comparing things that we have no business comparing.

There are two types of equality operators in JS which are used to return booleans (true or false) for conditional operations: the loose equality operator (==) and the strict equality operator (===). The distinction matters because the JS engine is too nice. It will attempt to perform a type conversion to make the two values comparable, if it thinks it can. This includes goofy things like changing ‘null’ to be a number.

42 == '42'

// => trueAs you’d imagine, this can have unintended consequences. The strict equality operator never performs type conversions, and should ALWAYS be your go-to for comparisons:

42 === '42'

// => falseWeird Thing 2: ‘this’ & Scope

At first, I thought ‘this’ in JS was similar to ‘self’ in Ruby, where it points to the object where the keyword is referenced. Not necessarily! In JS, where not everything is an object, the value of ‘this’ is specifically determined by whether or not it’s referenced within a method (i.e. a function that’s a property of a JS object). If ‘this’ is referenced inside a method, then its value is the object which received the method call. If it’s called outside of a method, its value is automatically the global scope. This can cause confusion in nested functions:

let person = {

greet: function greeting(){

function otherFunction(){

return this

}

return otherFunction()

}

}

person.greet()

//=> windowIf we had returned ‘this’ directly within person’s method greet(), we would have returned ‘person.’ Because person’s greet() method contains and ultimately returns the ‘this’ value of another inner function, otherFunction(), ‘this’ points to the global/window scope. This is because otherFunction(), which is the function that references ‘this,’ is not a method (it is not a function that’s directly a property of an object).

JS lets us explicitly set the value of ‘this’ to whatever we’d like, by using the call() or apply() methods:

let sally = {name: 'sally'}

function greet(customer) {

console.log(`Hi ${customer}, my name is ${this.name}!`);

}

let newGreet = greet.call(sally);

newGreet('Bob')

//=> Hi Bob, my name is sally!Similarly, to preserve the value of ‘this’ in callbacks, we can use bind():

const getUserInfo = function(callback) {

// ajax call to fetch data asynchronously

var numOfComments = 100;

callback({ comments: numOfComments });

};

const User = {

fullName: 'Mico Yambao',

introduce: function() {

getUserInfo(function(data) {

console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.fullName} and I made ${data.comments} comments`)

});

}

};

User.introduce();

//=> Hi, my name is undefined and I made 100 comments

//vs.

const User = {

fullName: 'Mico Yambao',

introduce: function() {

getUserInfo(function(data) {

console.log(`Hi, my name is ${this.fullName} and I made ${data.comments} comments`)

}.bind(this));

}

};

User.introduce();

//=> Hi, my name is Mico Yambao and I made 100 comments Weird Thing 3: Scope & Variable Declaration

Unlike Ruby (and many many other programming languages), JS variable declarations (at least with the original ‘var’ keyword) are function-scoped as opposed to being block-scoped. This can be confusing and unintuitive, especially when combined with another oddity, so-called JS ‘hoisting.’

Weird Thing 4: Hoisting & Variable Declarations with var vs. const/let

The JavaScript engine actually makes a couple of passes over code before execution. The first phase is called The Compilation Phase, in which it goes through the codebase from top to bottom, allocating memory to variables and functions (the engine reads and makes note of variable and function declarations) but doesn’t yet execute any of the code. In other words, it’s a preparation phase to make sure that the browser has everything in place for when the code actually executes. The second phase is called The Execution Phase, and this is when the code actually runs.

Therefore, something like this:

castFiraga();

function castFiraga () {

return 'You got burned!';

}

// => "You got burned!"…will work just fine even though the function invocation is written before the function declaration. This is because, during The Compilation Phase, the JS engine has already read and devoted memory to the function declaration (function castFiraga() { ... }). Thanks to this previous phase, during The Execution Phase, the JS engine already knows what the first line of code, the function invocation, is referring to. Because the function declaration, in JS engine chronology, takes place at the top, even though it is written in the code last, this behavior is called ‘hoisting’ (because it’s as if the declaration is lifted, or hoisted, to the very top).

Once again, the JS engine’s behaviour is implemented to try to help the programmer, however, this can be confusing because variables and functions that you had intended to refer to one thing, may haphazardly already exist and refer to other things.

This can be especially buggy in loops:

var array = ["chocobo", "mog", "malboro"];

for (var i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

var creature = array[i];

setTimeout(()=> { alert(creature); }, i*1000);

}

// => 'malboro', 'malboro', 'malboro'As the programmer, one would expect this function to alert ‘chocobo’, ‘mog’, ‘malboro’ for each of the array indexes at each iteration of the loop. The reason why this isn’t so, is because the JS engine hoists the ‘i’ and ‘creature’ variable declarations outside of the loop (remember, variable declarations with the ‘var’ keyword are function-scoped, not block-scoped). The setTimeout() callback function references these now globally-scoped variables. Because callback functions are asynchronous, the loop therefore runs to completion culminating at the third iteration and sets the ‘creature’ variable outside of the loop to ‘malboro’ before any of our alert callbacks are executed. When they are executed, they reference a variable all pointing to the same value because the loop has already run its course.

The solutions to hoisting problems are pretty simple:

1) always declare variables and functions at the top of your scopes so things are intuitive and predictable

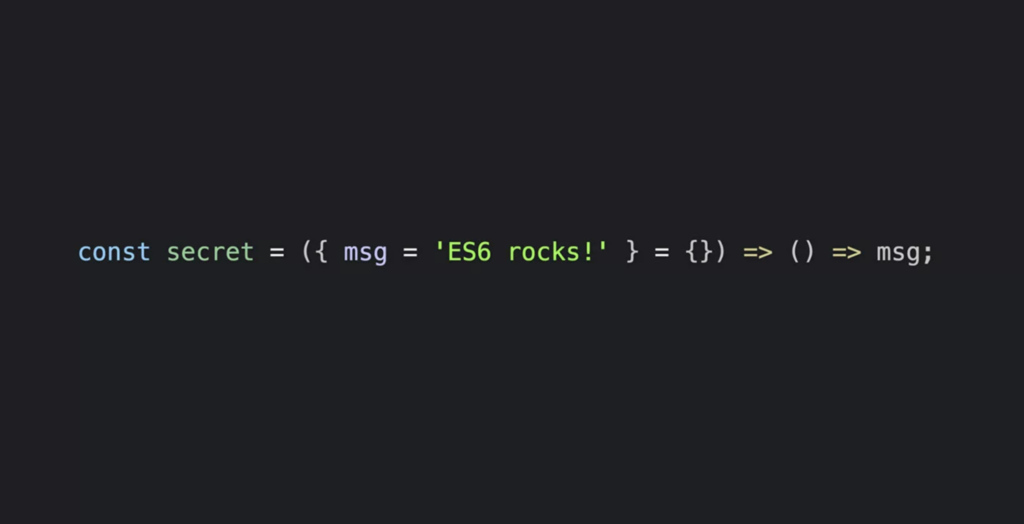

2) always declare variables and functions with the new ES6 keywords ‘let’ or ‘const’ (standing for ‘constant,’ declare variables with this keyword when you expect/want its contents to remain the same).

The fix to the above code is pretty easy, thanks to ES6’s ‘let’ and ‘const’ keywords:

const array = ["chocobo", "mog", "malboro"];

for (let i = 0; i < array.length; i++) {

let creature = array[i];

setTimeout(()=> { alert(creature); }, i*1000);

}

// => 'chocobo', 'mog', 'malboro'Unlike the ‘var’ keyword which declares things in function-scope, the ‘let’ keyword declares things in block-scope, as is more intuitively expected (i.e. in this case, the ‘loop’ scope). Therefore, in the code above, each iteration of the loop is a new ‘i’ assignment within the loop, as is with ‘creature,’ as intended.

Not only acknowledging that these oddities exist, but understanding why they exist, can go a long way to writing better code, and fully unlocking the potential of a programming language.

I do believe all of the concepts you have offered for your post. They are really convincing and can definitely work. Still, the posts are very quick for beginners. Could you please prolong them a little from subsequent time? Thanks for the post. Margret Moore Xylina

Like!! Really appreciate you sharing this blog post. Really thank you! Keep writing. Athene Dene Jocko